Turnout for What?: An altogether different concern with field experiments

To the degree that Political Science Twitter can blow up, it

blew up this week with the controversy over a field experiment run by

professors at Stanford and Dartmouth in Montana (For the latest in the debate, see

John Patty; for overview, Derek Willis in

NYT). I don’t have anything to add to the ethics in field experiments

discussion, although I am sympathetic to the accused profs. (If you would like

a totally ethical look at how information increases participation in races like

these, see

my MPSA paper from last year!)

My concern with this episode is that it illustrates a

problem with the literature on turnout studies. They’ve gotten too good. One

only needs to look around at the mail parties send to voters to see that

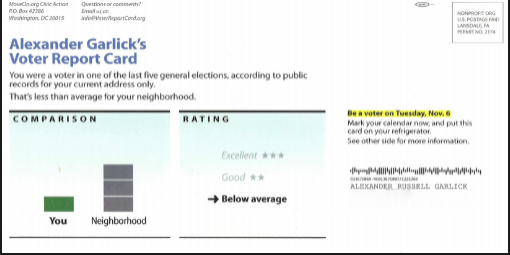

voter shaming (like in Alaska), and possibly intimidation, is alive and well. These are

techniques that were first tested by field experiments.

(Look, it even happened to me in 2012)

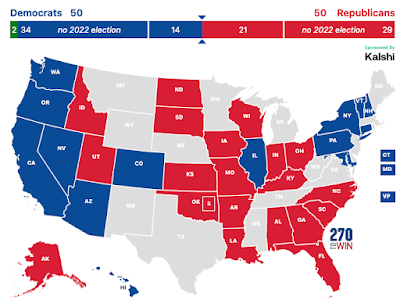

The combination of these techniques and the robust field

office infrastructure of the Obama campaign means that voters in competitive

races are being inundated with campaign contact in the last few days before

election day.

Updated report: new data shows voter contacts up "a whopping 54% over this time period in 2010." http://t.co/Djrta6laaz via @techPresident

— NGP VAN (@NGPVAN) October 30, 2014

The problem is that increasing effectiveness of these techniques is approaching the ceiling. The concept from economics of diminishing marginal returns applies. Consider television ads, if you’ve seen 50 ads the 51st ad has little impact on you. With social pressure, the first postcard you get may make a difference. The tenth postcard that compares your voting record against your neighbors has little impact. If anything the Montana case shows that it may be putting voters off.

So I doubt that these techniques are going to move the needle much in the future. But they're not going away. American

politics is a zero-sum game; so if one side is doing it, the other needs to be

doing it too. Therefore, campaigns (and researchers) will surely be looking for the next new innovation that gives them an edge.

Ultimately, that’s why field experiments need to survive

this current scandal. The lasting contribution of the turnout field experiments

is not shaming techniques or that in-person contact is better than mail.

The real innovation is it demonstrated the power of a systematic method of randomly assigning some voters

to receive a treatment and comparing them to others. When I worked on campaigns

we did everything we could think of to influence voters and just hoped it work.

This political science research program has shown how to do a much better job of

that. That's why it needs to survive this onslaught from critics.